Data tells us:

Key Factors:

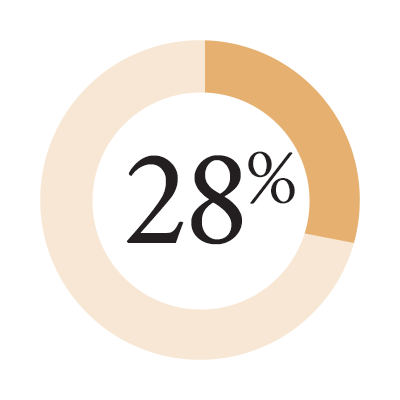

Growing Residential Segregation by Income

Low-income children today are twice as likely to live in neighborhoods and communities segregated by income as they were in 1970. As income disparities grow, and as more families seek to live in the best school districts, low-income children further concentrate in schools, making it less likely for high-performing students to get the needed attention as teachers and administrators concentrate on developmental delays and challenges among students struggling to reach the proficiency level.

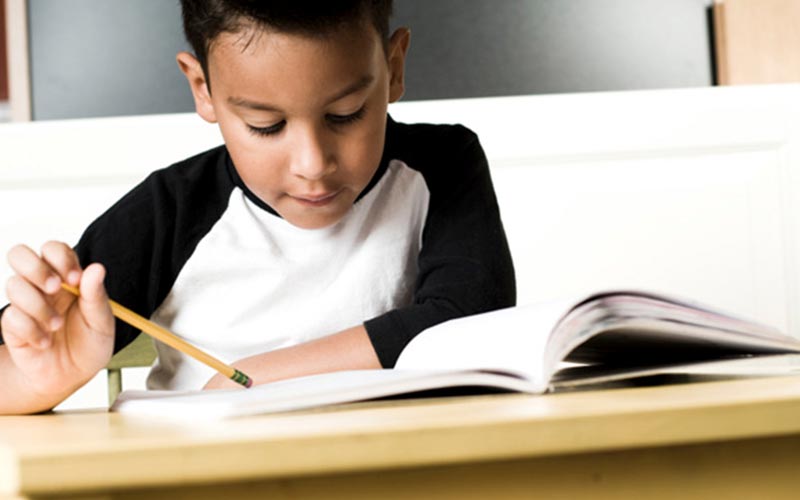

Access to High-Quality Day Care and Preschool

According to National Center for Education Statistics data, only 20 percent of 4-year-olds in poverty can recognize all 26 letters, compared with 37 percent of their peers at or above the poverty level. Along with availability and cost of high-quality day care and preschool, new research shows that the literacy challenge extends to early childhood educators themselves — as many as 1 million state-licensed and nationally-credentialed early-childhood educators are at-risk for functional illiteracy; their reading and writing skills are inadequate to manage daily living and employment tasks that require reading skills beyond a basic level.

Isolation

For families with access to fewer resources such as libraries, healthcare services, or daycare centers, putting all of the pieces together to prepare their children for school can be very difficult. Those living in rural areas are particularly susceptible, although low-income urban areas lacking proper public transportation often suffer the same fate. New research shows that high-income parents spend more time than low-income parents in literacy activities with their children, especially when it involves “novel” places — settings away from home, school, or care providers. Between birth and age six, children from high-income families spend an average of 1,300 more hours in novel contexts than children from low-income families (Phillips, 2011). Such experiences contribute to the background knowledge considered critical for mastering science and social studies texts in middle school.

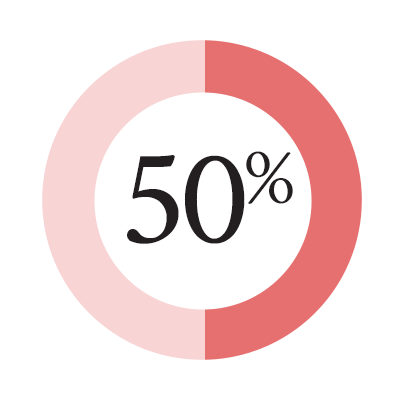

Food Insecurity and Other Stressors

More young students come to school with poverty-related challenges — ranging from chronic stress and exposure to trauma, to food insecurity — all of which have short- and long-term consequences for their educational trajectories, including the most advanced learners. According to most recent data, at least 48 percent of all American public school students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch (which includes families above the poverty line) — a record high number. Food insecurity has been linked with delayed development, poorer attachment, and learning difficulties in the first two years of life.2 Long-term poor nourishment can affect a child’s physical development, further undermining other factors.

What works:

Earlier Intervention

The Affordable Care Act in 2010 created the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting program (MIECHV), which helps states pay for programs that pair at-risk mothers with trained professionals who visit families’ homes. The creation of this new federal program will support children in the 0–3 age range, a critical period for language development and early literacy skills. Research shows that lower-income parents are often simply unaware of resources available to them, do not have all of the facts about preparing their children for school, and are not encouraged to do so. Consistent outreach efforts, including parental training, can help dispel myths and connect parents to the right resources.

Full Day Kindergarten

Kindergarten is typically overlooked by policymakers, though research shows children benefit from high-quality, full-day kindergarten and kindergarten is the starting point for later rigor. Only 11 states and the District of Columbia statutorily require all school districts to provide publicly funded full-day kindergarten; six states do not require districts to provide kindergarten at all, and the rest require at least a half-day of kindergarten to be provided. Estimates for the percent of children who attend some type of full-day kindergarten range from roughly 58 to 77 percent, but in some cases, the second half of the day may be supplemented by parent tuition payments. In recent years, some states — including Minnesota, Oklahoma, Washington, and Nevada — have started to expand the provision of full-day kindergarten.